Why Are Pressure Injuries Harder to Prevent Than Other Hospital-Acquired Conditions?

Pressure injuries remain one of the most preventable hospital harms—so why do they keep happening?

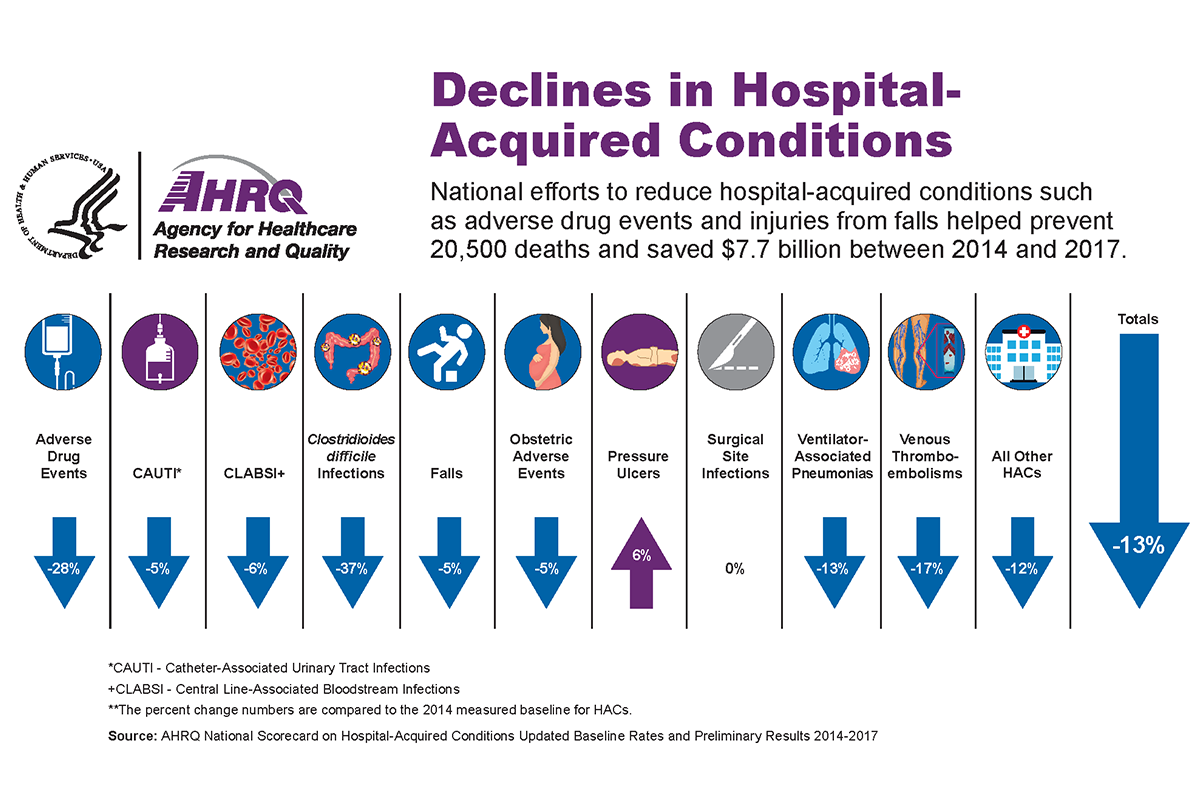

Unlike many hospital-acquired conditions (HACs), such as central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) or catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), pressure injuries are not solved with a single intervention or medication. They require constant vigilance, nuanced clinical judgment, and a complex system of caregiving staff to protect patients who cannot protect themselves.

The Scope of the Problem

A recent meta-analysis estimates an overall hospital prevalence of ~12.8% and a HAPI incidence of ~8.4% (Li et al., 2020 →). In critical care, prevalence ranges from 10% to 45.5%, with incidence up to 41% (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 2024 →).

The economic burden is equally significant. Each case costs anywhere from $20,900 to $151,700, with annual U.S. costs estimated at $9.1–$26.8 billion (AHRQ, 2017 →; Padula & Delarmente, 2019 →). Medicare has estimated an added $43,180 per case (Tomlinson, 2024 →).

Beyond dollars, the human toll is staggering: patients endure pain, infections, longer hospital stays, and in severe cases, death from infection of wounds. Families, too, suffer the emotional weight of seeing a loved one harmed in what should be a place of healing.

Why Pressure Injuries Stand Apart

So, what makes pressure injuries more difficult than other HACs? The difference lies in their complexity and invisibility.

- Multifactorial risk.Unlike an infection linked to one device, pressure injuries arise from immobility, friction, shear, moisture, nutrition, perfusion, and a myriad of medical comorbidities. Nurses must balance dozens of variables to assess true risk (Li et al., 2020 →).

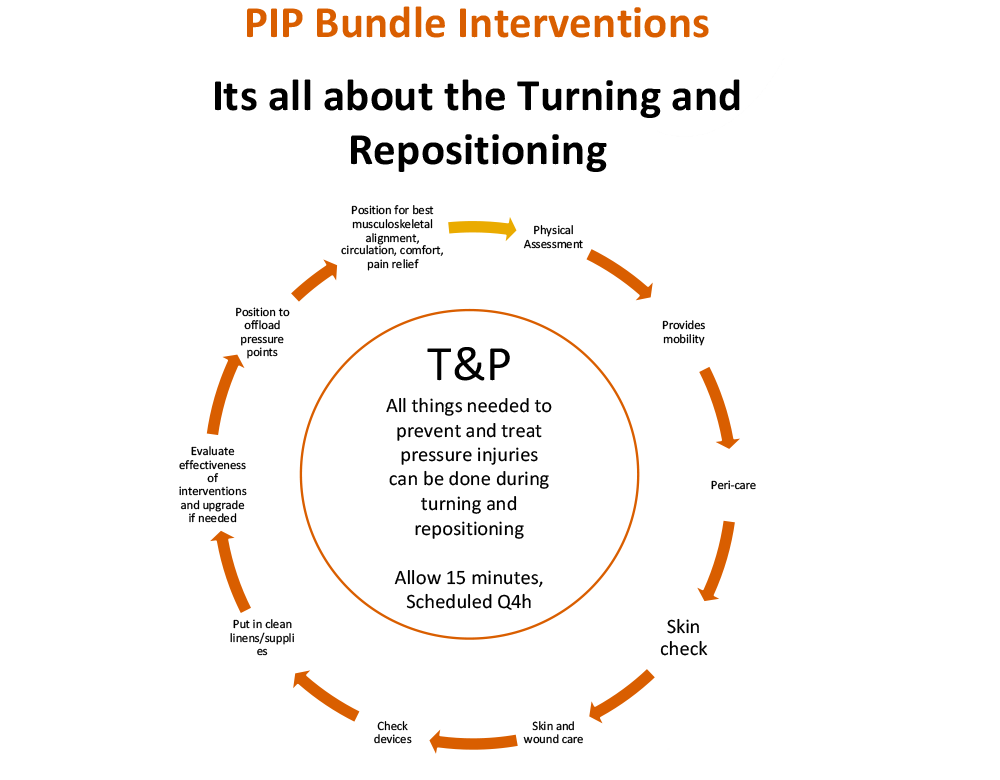

- Constant vigilance required.A CLABSI prevention bundle can be standardized; a patient’s skincare and mobility cannot. Preventing pressure injuries requires continuous repositioning, monitoring, and timely interventions. If a patient shifts even slightly in bed, risk dynamics change.

- Difficult detection.Early-stage pressure injuries often form beneath the skin before any visible surface damage appears. By the time redness or breakdown is seen, damage may already be severe.

- Staffing and workflow challenges.Prevention is highly labor-intensive. Repositioning, skin checks, and moisture management compete with countless other urgent demands on nurses’ time, particularly in understaffed units. ICU burden illustrates this clearly: prevalence is among the highest in healthcare, with improvement only after ICU-specific risk tools and interventions (AACN, 2024 →).

The Human Side of Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries highlight the intersection of clinical complexity and human vulnerability. They often occur in patients least able to advocate for themselves—those sedated, immobilized, or critically ill. Unlike an infection that can sometimes be “fixed” with antibiotics, a pressure injury can prevail for years, leave permanent scars, disability. Even those that heal are vulnerable to break open again for the same reason they occurred in the first place.

For frontline staff, this is more than a checklist issue. Effective intervention is highly variable, laborious, time consuming and fraught with complications. It’s a moral injury when harm occurs despite best intentions and enormous effort. For patients and families, it’s a betrayal of trust when safety slips through the cracks.

Steps Toward Real Prevention

Reducing pressure injuries requires more than compliance with risk assessment tools. It demands a cultural shift in how hospitals view prevention:

- From a separate obligation to a routine, proactive core practice.All too often systems want to fall back on an “every 2 hours” protocol. This assumes that nurses work is such that they can stop what they are doing to go to another room to turn and reposition. When in fact, mobilizing and managing patient position, moisture and nutrition is a routine core practice that should be done when the caregiver is in the room. Treat repositioning and skin protection as essential, not optional, parts of care.

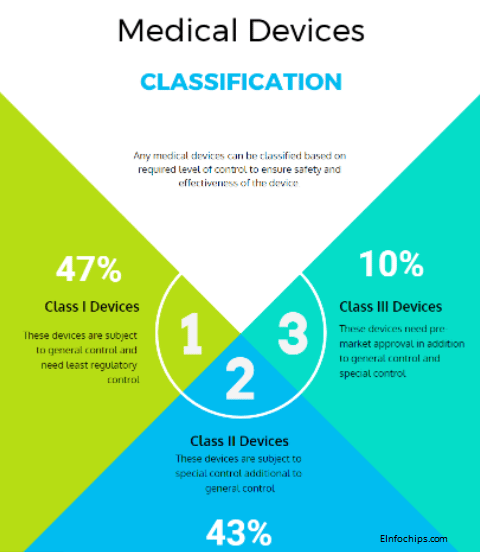

- From fragmented to systemic.Provide the right equipment—specialty mattresses, positioning wedges, moisture barriers—and ensure they are consistently available.

- From individual to team-based.Recognize that it usually takes 2 caregivers to perform turning and repositioning interventions. it requires coordinated, organized and adequate staffing.

Pressure injuries remain one of the hardest HACs to solve precisely because they expose both the limits of medical interventions and the fragility of human care systems. But they are not inevitable. With focus, resources, and accountability, hospitals can reduce their prevalence—protecting not just statistics, but real people whose health and dignity depend on it.

To download The Ultimate Guide: How to Stop Bedsores, click the title or click here.

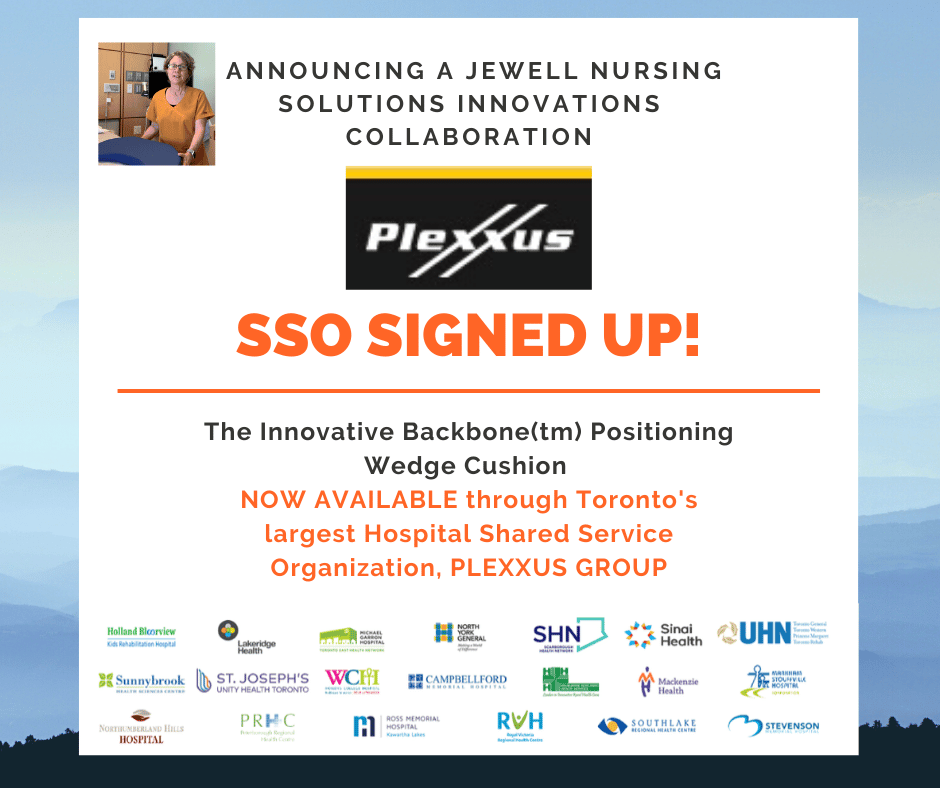

- Gwen Jewell, of Jewell Nursing Solutions, is a wound care specialist and has a passion for seeking solutions to reduce pressure, keep patients more comfortable, and assist nurses in the fight against pressure injuries.

Jewell Nursing Solutions’ mission is to empower all caregivers to prevent and heal pressure injury wounds. For more information, contact us HERE.